What’s Important Now?

by Michael LeFevre

Managing Editor, DesignIntelligence

July 12, 2023

Success is not about balancing priorities – it’s about having them. How do we get better at setting priorities and reacting to change in an uncertain world?

In our quest to make sense of a frenetic world, the discussion often returns to phrases such as “work-life balance,” “juggling balls,” “spinning plates” and “balancing priorities.” But here’s the thing: Being successful and productive is not about “balancing” priorities, it’s about having them. “Priority” means “this is more important than that.” The word’s root is prior, as in “comes before” or “is more important.” Easy. But how do we decide what’s important in an uncertain world? To begin, it might help to look at how we derive meaning and influences and assign values.

Context Matters: Where Good Ideas Come From — “The Adjacent Possible”

To continue our look at contextual awareness begun in Q2’s DesignIntelligence Quarterly, we would be well served to understand that importance finds its meaning in context. Beyond and before assigning weights to things, in the creative fields our challenge is often to expand the context and investigate countless alternatives. But in doing so, we only add to the list of things that must be prioritized. Yet, that’s usually our job. To understand how and where we find new ideas, a helpful reference for designers working within many contexts is “Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation” by Steven Johnson. Multiple contexts allow exploration of what Johnson calls “the adjacent possible” or opening the easily accessible combinatorial doors of nearby spaces. Johnson explains, “Good ideas are not conjured out of thin air. They are built out of a collection of existing parts, the composition of which expands (and occasionally contracts) over time.” To find more parts we must push beyond the edges of our normally traveled routes, seek new inputs and enter new rooms. Johnson adds, “The trick to having good ideas is not to sit around in glorious isolation and try to think big thoughts. The trick is to get more parts on the table.”

But how does new information flow? Per Johnson, in “liquid networks that become the medium for the flow of ideas and connections,” media that allow fluid exchange create environments and cultures conducive to innovation. Johnson calls it “primordial soup.” Only in such fluid environments can we go on “long and fruitful tangents” to achieve the random connections, serendipities and “generative chaos” innovation requires.

Serendipity is just one such state, a condition resulting from a hunch waiting to make a connection or being in the right place at the right time, sensitized and ready to receive the surprise, the “happy accident.” One good way to break logjams and find surprises in our thinking is to go for a walk. History tells us that a good many discoveries were prompted only by leaving the work at hand and changing perspectives. How wonderful. One of the best ways to increase contextual awareness is to change our own context and take a break – to simply let “life” happen.

Some of these leaps and connections are possible, “but only because a specific set of prior discoveries and inventions had made them possible,” per Johnson. This prerequisite often applies to ideas that are said to be “ahead of their time.” The context and conditions are simply not ready to receive them yet.

We can conclude, then, that the contexts of our time, our epoch and our predecessors are keys to contextual mastery – and setting priorities. We must know history and, sometimes, be patiently persistent.

Being “Wrong”

Another long- and well-understood principle in design circles, being “wrong” offers great benefit. The rituals of “investigating options,” “exploring blind alleys” and “noodling with ideas” have long been part of design’s trial-and-error method – a routine in which we learn from our mistakes and eliminate certain contexts. Steven Johnson suggests “transforming error into insight” as a more erudite way to describe the process. Just over a hundred years ago, in 1922, even T.S. Eliot wrote of the value of going in circles in his epic poem, “The Waste Land”:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

T.S. Eliot

“Little Gidding” (the last of his “Four Quartets”)

You won’t find a more pragmatic and poetic example of contextual awareness (or knowing what’s right when we see it) for the second time.

Exaptation and Stacked Platforms

Evolutionary biologists have coined a word that seems helpful to describe another mode of idea generation: “exaptation.” The term describes appropriating a concept developed for one purpose and using it for another. Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press is an example. By taking the screw press from winemaking and adapting for use in his printing press, “he took a machine designed to get people drunk and turned it into an engine for mass communication,” per Johnson.

Here’s some good news: Modern-day, contextually aware designers can now rely upon what computer programmers call “stacked platforms” to increase the velocity of acceptance and usefulness of their ideas. Think of them as stepping stones, tools or systems that rely upon one another to enable and accelerate work. Via stacked platforms, you no longer need to know how to write computer programming code on your own, how to design a computer or why. You simply use a friendly graphical user interface or the power of Google’s search engine to do your research for you via connected, already-developed technologies. Think of them as nested “contexts” of their own.

Ranking Basics: The Eisenhower Grid

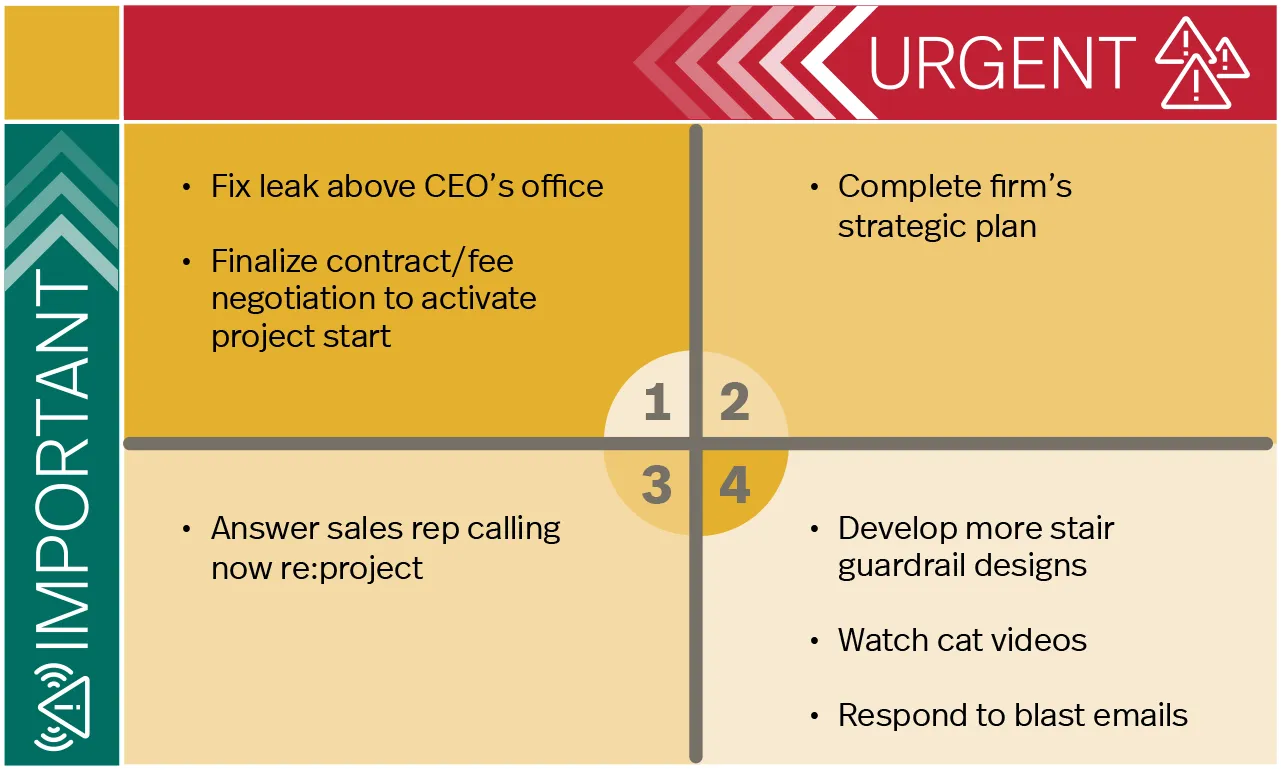

But back to our problem, having generated countless concepts and lists of things that could and should be done, how do we best approach the winnowing process to evaluate and rank our possible actions? One of the most widely used devices is an old chestnut called the Eisenhower Matrix, also called Box, Grid or Prioritization Framework. It was used by our former president Dwight D. Eisenhower. In this four-square matrix, possible actions are classified on two scales: urgent and important. Analyzing decisions and actions against these two axis scales helps you place possible tasks in the quadrants as one of four types: things you’ll do now, schedule for later, delegate or delete. Urgent and important things are placed in Quadrant 1 (upper left in the grid). Important but not urgent tasks such as long-range planning are placed in the upper right, Quadrant 2. Urgent but not important elements like interruptions, distractions and phone calls are logged in the lower left box. Finally, items that are not important or urgent (such as trivia, busywork and time wasters) are tucked into the lower right box. With this simple analysis tool, deciders can easily see which things to work on first.

Eisenhower Grid

Eisenhower Grid

A variation on this approach is to go through your list and triage it. Classify tasks as Priority 1s, 2s or 3s. Then, cycling through the list again, establish a rank order of urgency within each set of 1s, 2s and 3s. If you’ve done this digitally, say, using a spreadsheet, you’ll find it easy to re-sort your items and clearly set one thing as the priority – the thing that must be done now.

What to do next? Hundreds of successful management experts from Peter Drucker to H. Ross Perot to Tim Ferris have advocated one simple approach to the next task. Having classified and evaluated the possible actions, select the one most critical, the one you’ve decided must get done now or it will invoke dire consequences. Then, work only on that one until its done and then move on to the next one. One thing. Not two. Not six. Not 27. No distractions. Just what’s important now.

Shift Happens

With such a seemingly simple system for setting priorities, why is doing it so hard? Because shift happens. Things change. No sooner than you’ve set your priorities and set about accomplishing that one thing you have deemed most important, a client calls ... there’s a leak … we need your input on a business development proposal, the biggest project in firm history … your daughter has been in a car accident … What to do? How to react?

When someone introduces change into our well-laid plans, we are faced with a recurring dilemma: Do we do X, or do we do Y? A or B? You see, resetting and reevaluating priorities is the art and the science of setting them. It’s the magic skill that requires judgment. How do we cope with such change?

Deciding Amid Dynamic Contexts

There is nfo shortage of expert planners who become frustrated and grind to a halt when their best laid plans get reprioritized by external unanticipated events. Shame on them. As leaders, we should know by now that, like rules, plans were made to be broken. Why then are we surprised when they inevitably, inexorably are? Clear thinkers set priorities, fully expecting to have them changed and fully prepared to respond when they are. Football teams fumble. Then they try to get the ball back. Things happen, and they expect them to. Be ready for it.

Contextual and Cultural Awareness

Perhaps the single greatest reason for failure of priority-setters is failing to include the right folks in their thinking and process. Priorities set devoid of context or unaware of the culture in which they will operate are doomed. Look around. Involve the right folks.

Best Practices

After a half-century as a successful priority-setter on Planet Earth, I’ve gleaned a few personal best practices. I’ll share them here.

1. Vision and Values

To begin with, to know where we’re going and to advance our progress, we need a clear, compelling vision. That vision must be a values-based, bold, aspirational, directional view of where we desire to go. Visions that don’t stretch us, are directionless, vague and nonspecific are of little value, even harmful. Value-based visions can result in a strategy and set of tactics. At each turn we can ask: Does this action support the vision, the mission, the strategy? If not, we can assess if it’s time to revisit the vision or to hold our ground. As leaders, making those judgments is what we get paid for. These leadership acts of seeking and anticipating change qualify us to lead. We must make them well.

2. Balance

Is balance required? Well, after decades of misdirected advice from countless experts, we’ve uncovered a few myths. First, there is no such thing as work-life balance. Work and life are inseparable and integrated. Or they should be. It’s only how you choose to spend your time in your current context that matters. In this moment, a radical imbalance of work and life and might be in order because of a short-term deadline. Setting that as the priority doesn’t mean you’ve changed your mind about the importance of your family and friends, just that you’ve set them aside for the moment. There is no work-life balance, they’re all together in a great big mashup called “your life.”

3. Single-Tasking and Focus

Despite what the youngsters would have us believe, there is no such thing as multi-tasking. Sure, we may have five programs open on our computer; we may have 11 file folders open on our desktops; we may be sitting in a boring Zoom meeting and daydreaming about another project or sitting in front of the television and reading the latest important news about Kim Kardashian on our iPads. But, in truth, experts tell us we can only focus on one thing at a time. Set your priority and do that one thing well, they advise. Be present for it (or them). If being on vacation is most important now, then do that well and only that.1

Credibility Calls. Life Awaits.

While architects and designers are coveted for our abilities to wrestle with uncertainty, explore options and make creative leaps, we must learn to perform these skills under control, in moderation and at the right times. I have seen too many projects fail because their designers (myself included2) were unable to set priorities. In these instances, with the project on the brink of failure due to being over budget or past due, the lead designers and responsible parties whiled away their time doing frivolous handrail details. Needless custom confabulations were generated where other matters demanded attention first. No more. Until we learn how to set priorities like the rest of the world, we will keep ourselves firmly seated at the children’s table of professional power and responsibility. Those of us who lack the discipline of critical thinking must learn it quickly or align ourselves with someone who already has it. In our daily human quests to make sense of the world and shape it into our own realities as leaders, making choices is what we do.

Life (and credibility) awaits.

They are important.

Now.

Michael LeFevre, FAIA emeritus, is managing editor of DI Quarterly and principal DI Strategic Advisory. His breakout book, “Managing Design: Conversations, Project Controls and Best Practices for Commercial Design and Construction Projects” (Wiley 2019) was an Amazon #1 bestselling new release.

FOOTNOTES:

1 Author’s Confession #1: A Personal Anecdote

When cell phones became widely adopted in the 1990s I was a reluctant late-adopter. I feared being constantly connected would render my valuable personal time into a never-off-duty, faster-turning squirrel cage of business and cause an imbalance in the hypothetical “work-life balance.” But, for me, the opposite was true. Even on vacation at an all-inclusive island resort, being connected via cell phone was hardly an intrusion. Surprisingly, it kept me easily connected to what was happening at work through quick occasional peeks at my email and voicemail messages. Being “in the know” armed me with real data and allowed me to stop wondering, forget about work and relax. Technology afforded me the luxury to remain true to my current priority: to recharge with family and friends.

2 Author’s Confession #2: Having witnessed and studied the struggle to think clearly for decades, I took it upon myself to take a personal journey and share my findings. My legacy investigation, “Managing Design: Conversations and Project Controls for Commercial Design and Construction Projects” (Wiley, 2019), is a collection of interviews with leading industry thinkers on the subject. In this “Noah’s Ark of perspectives,” two voices each from a broad continuum of disciplines (architecture, engineering, construction, academia, trade contractors, technology, etc.) share their thinking on how to do the impossible: set priorities, think clearly and manage design. To coalesce the discussion, the book’s second half offers a conceptual model for balancing the many considerations entailed in managing design. I call it the Project Design Controls Framework, a memory palace for cognitively mapping the many priorities – hard and soft – that affect managing creative processes.